introduction

This site is my final project for the first semester of Mrs. Reyes’s multivariable calculus course! It’s hosted by GitHub Pages at this repository, and is built with Jekyll and written in Markdown. Here’s the presentation I gave in class.

For my project, I’m focusing on exploring a specific subset of topological spaces called non-orientable manifolds, their definitions and fascinating properties, and their connection to multivariable calculus. Topology has a lot of jargon, so I’ll quickly go over some basic definitions so everything is relatively easy to understand, but it probably means that I’ll be making some simplifications and saying things that are only technically accurate. In addition to drawing connections between Klein bottles and multivariable calculus, I’ll also discuss other non-orientable manifolds, topology topics, and some differential geometry like parametrizing surfaces. My goal is to provide a broad, interesting glimpse into the amazing world of topology through an interesting topic.

Connections to multivariable calculus:

- multivariable functions (chapter 15.1)

- parametrizing surfaces (chapter 11.2, 17.6)

- orientability (17.2, 17.4)

- changes of variables (chapter 16.9)

artwork

Work in progress.

To Mrs. Reyes: for my final project, I’m submitting this website as the product instead due to time pressure, although I will still complete the artwork because I think it’d be fun to submit to SHSPMC. It’s just not part of the scope of my final anymore.

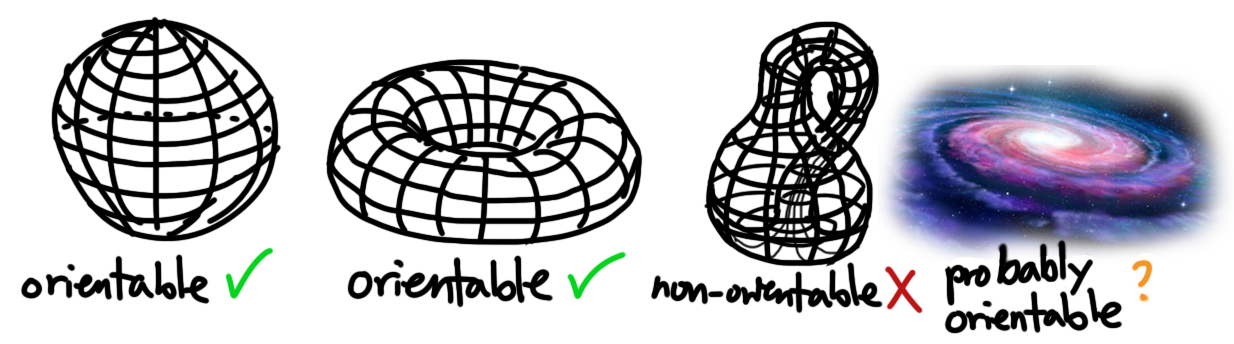

what is orientability, anyway?

To understand non-orientable manifolds, we can break the term into two pieces: defining orientability and defining manifolds. (Sadly, this strategy doesn’t necessarily work for all math concepts, like the “hairy ball theorem” and “space curves.”)

In topology, a manifold is a topological space which locally resembles Euclidean space near each point, meaning that no matter how far you zoom in to a point, the neighborhood of that point still preserves all the topological properties of its mapping in $n$-dimensional space. Some example of 1-dimensional manifolds are lines and circles. Surfaces are simply 2-dimensional manifolds, so for this project when we talk about non-orientable manifolds/surfaces, for all intents and purposes, they’re basically the same thing. An $n$-manifold is simply a thing that lives in $n$-dimensional Euclidian space (it’s more nuanced than this, but it’s close enough). Manifolds are common in geometry, topology, and other fields as solution sets to systems of equations and graphs of functions, which is how we’ll be using them.

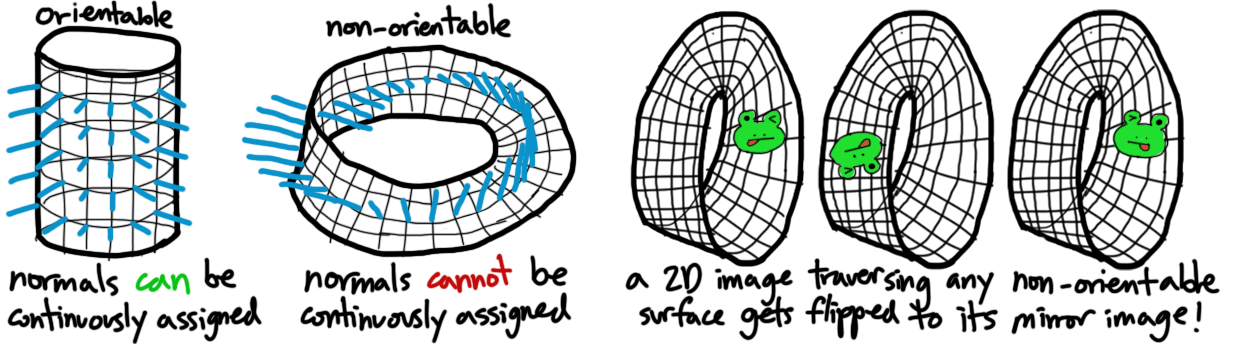

There are a couple ways to think of orientability: the formal definition is that it’s a property of topological manifolds which permits a consistent sense of clockwise and counterclockwise. Intuitively, this means that if you choose a direction of a normal vector and keep assigning normals along the surface, when you loop back around to your starting point the normal vector should still point in the same direction. Another definition is that a surface is orientable if and only if it contains a Möbius strip.

Side note: orientability is also a concept for curves. Curve orientation is simply the choice of which direction you travel along the curve. It’s a particular case of the concept of orientability for a manifold. For example, the x-axis pointing right and y-axis pointing up are technically chosen orientations. Closed curves can either be positively/counterclockwise oriented or negatively/clockwise oriented.

In popular mathematics, a surface that’s non-orientable is usually described as having only one side, probably because that’s the most exciting way to introduce the concept. You can imagine an ant walking along the surface of a Klein bottle: starting on the “outside”, the ant can crawl through the tube and onto the “inside” of its starting point without ever crossing a boundary or edge. This means that surface only has one side, and there is no notion of “inside” or “outside.” That’s pretty neat!

The formal definition is basically the opposite of orientability: it’s a property of a surface where you can’t consistently define clockwise and counterclockwise. If you try assigning normals like on an orientable surface, when you get back to your starting point the vector will be pointing in the opposite direction. Or, if a 2D object travels along a non-orientable surface, it will return mirrored.

On a non-orientable surface, you can’t integrate vector fields (e.g. surface integrals, line integrals) because you can’t reconcile the inconsistent surface normals. You can still take multiple integrals and things like that, to find volumes.

Now that we’ve got a basic understanding of non-orientable manifolds, let’s focus on my favorite one: the Klein bottle.

the one and only klein bottle

Named after Felix Klein, who described it in 1882 (linked in case you want to make fun of his picture).

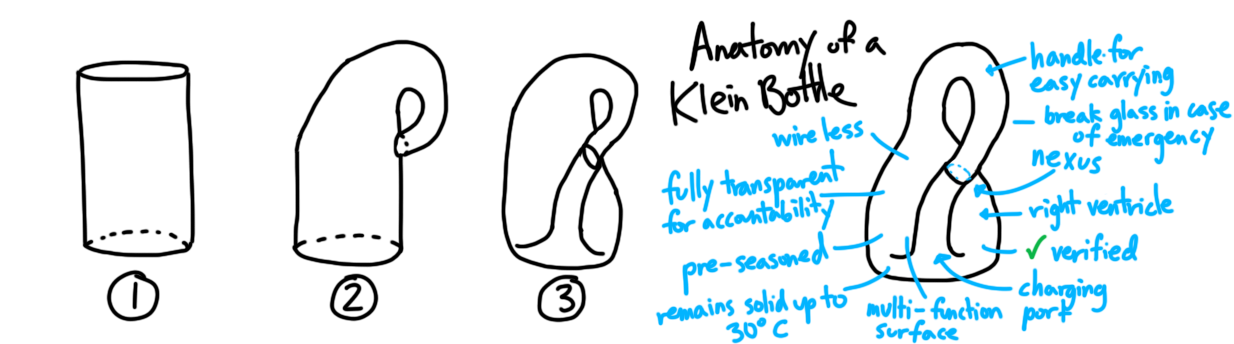

Constructing a Klein bottle is simple - it’s just 3 steps. Take an open cylinder, extend one end of it and bend it around to go back through itself, and smoothly connect the ends. Did you follow along? Awesome! You now have your very own Klein bottle.

Alternatively, a Klein bottle can be constructed via the sophisticated, rigorous mathematical technique of taking two Möbius loops and gluing them together. As Leo Moser puts it:

A mathematician named Klein

Thought the Möbius band was divine.

Said he: “If you glue

The edges of two,

You’ll get a weird bottle like mine.”

Let’s do a quick rundown of some amusing, fascinating facts about Klein bottles:

- one-sided surface

- zero edges

- zero volume (perfect for consuming technically zero alcohol)

- 2D manifold immersed in 3 dimensions for us lowly humans to observe, but can only be embedded in 4 dimensions

- composed of two mirror-image Möbius strips glued together

- pretty easy to fill, almost impossible to empty

- Euler characteristic of 0, given by vertices - edges + faces

- genus of 1, loosely meaning it has one hole

- non-orientable genus of 2

Those first three are the most well-known properties, so let’s break them down. We know that a Klein bottle is one-sided from when we defined non-orientability: you can’t consistently assign normal vectors along the surface, so there’s only one side (again, imagine the meandering ant). Next, if you have two pieces of paper and connect them, the edges that have been joined are “lost”. So what if we do the same with Möbius strips? Well, each strip has one edge, so if we connect them, both should be lost: we end up with a surface that has no edges - the Klein bottle. Neat! Finally, the Klein bottle also has zero volume because it doesn’t separate the universe into two parts.

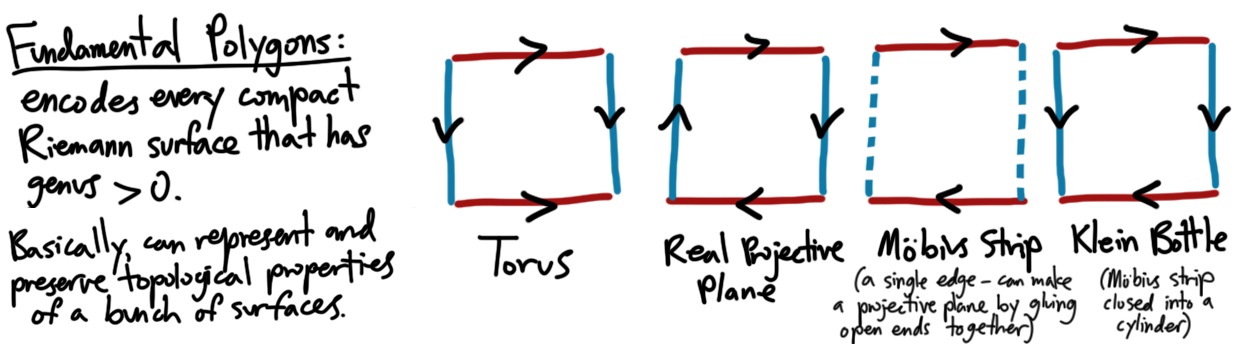

Yet another, more generalized and abstract way to define one: The solid Klein bottle is the non-orientable version of a solid torus. The Klein bottle’s fundamental polygon, along with a couple other common ones, are given below.

The way the opposite arrows are flipped for the non-orientable mirrors what we said earlier: if you take an image and traverse it across the surface, it will come back reversed.

Ok, so we understand what a Klein bottle is conceptually. The nice thing about topology is that it doesn’t matter how we bend, stretch, or twist our surfaces (known as continuous deformations), they still retain the same properties - this is why a coffee mug is topologically equivalent to a donut. We just can’t tear, glue, open/close holes in them or pass them through themselves. But what if we wanted to take away this freedom and look at some equations that can give us an idea of what “version” of a Klein bottle we’re actually seeing?

This is where the multivariable calculus comes in. Clifford Stoll, topologist and purveyor of fine glass Klein bottles, offers the following parametrization of a Klein bottle as an alternative to buying one:

\[x(u,v) = \cos{u}\cos\frac{u}{2}(\sqrt{2}+\cos{v})+\sin\frac{u}{2}\sin{v}\cos{v}\] \[y(u,v) = \sin{u}\cos\frac{u}{2}(\sqrt{2}+\cos{v})+\sin\frac{u}{2}\sin{v}\cos{v}\] \[z(u,v) = -\sin{\frac{u}{2}}(\sqrt{2}+\cos{v})+\cos\frac{u}{2}\sin{v}\cos{v}\]Of course, since this parametrization has 3 variables, it represents an immersion of the manifold in $\mathbb{R}^3$ space, not an embedding. If this sounds confusing, a good way to think about it is that a photograph of a penguin is a 2D representation of a 3D penguin that’s been flattened: it’s been immersed in 2D space. In the same way, we’re taking a “photograph” of the Klein bottle one dimension down so it can exist in our universe which, alas, has only 3 spatial dimensions. The difference between an embedding and an immersion is that immersions allow self-intersections, but neither can have folds or cusps.

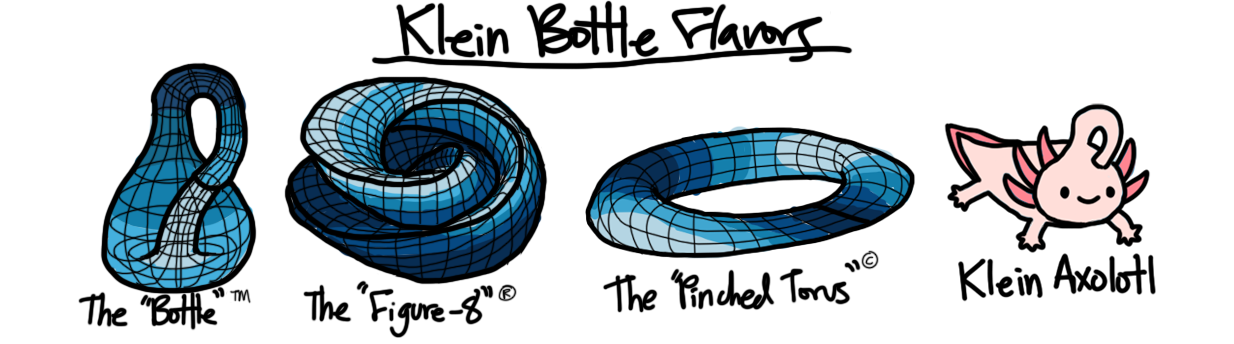

This particular immersion of a Klein bottle is pretty ugly, but that’s okay, because there are many others. There are 3 common forms a Klein bottle takes in $\mathbb{R}^3$: the classic “bottle” shape, the right-handed and left-handed figure-8 immersions (which are chiral), and a pinched torus.

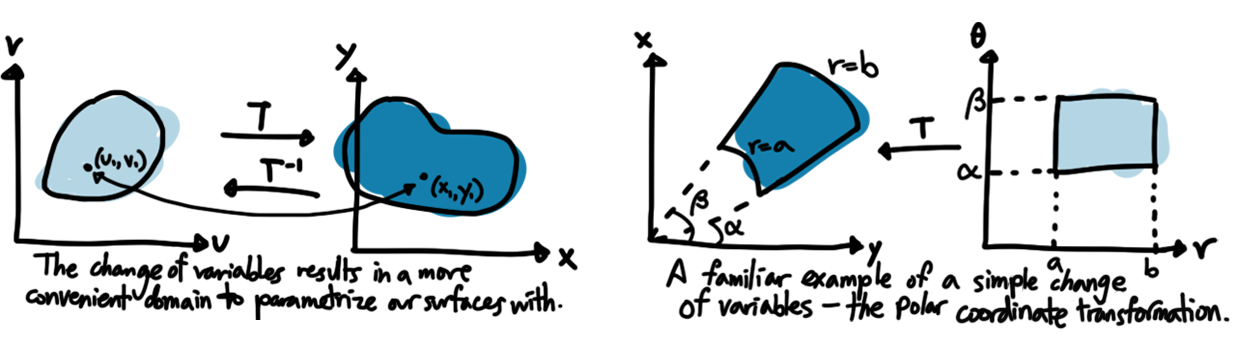

You might notice the parametric equations above are functions of $u$ and $v$ rather than $x$ and $y$: this indicates a change of variables, meaning we’ve taken the domain of some function and transformed it into another coordinate system that makes the domain of that function much nicer to look at. You’re probably pretty familiar with this general concept: $u$ substitution for differentiation/integration and polar coordinates are examples of change of variables. Some other useful changes of variables include transformations into cylindrical or spherical coordinates for multivariable functions. This is common when writing equations to describe topological spaces, since they’re so strange looking, and usually composed of surfaces of revolution.

Change of variables is a semester 2 topic from Chapter 16.9, because it’s useful in multiple integrals. Generally, we consider a change of variables from a $uv$-plane to the $xy$-plane through a transformation $T$: $T(u,v)=(x,y)$. It remaps the region to some other region that will hopefully simplify our parametrization, integral, or whatever it is we’re doing. If $T(u_1, v_1)=(x_1,y_1)$, then the point $(x_1,y_1)$ is the image of $(u_1, v_1)$. $T$ is called one-to-one if no two points have the same image.

It’s important to note that all the Klein bottles we see are 2D manifolds immersed in 3D space so we can visualize them. In their “true form,” they need to live in 4 dimensions so that they can pass through themselves without a hole - they have no self-intersection (also called a nexus). But here’s an idea: what if I wanted to break my brain and consider 4D parametrizations of Klein bottles and their 3D-immersed counterparts to try to get a glimpse of what Klein Bottles should look like?

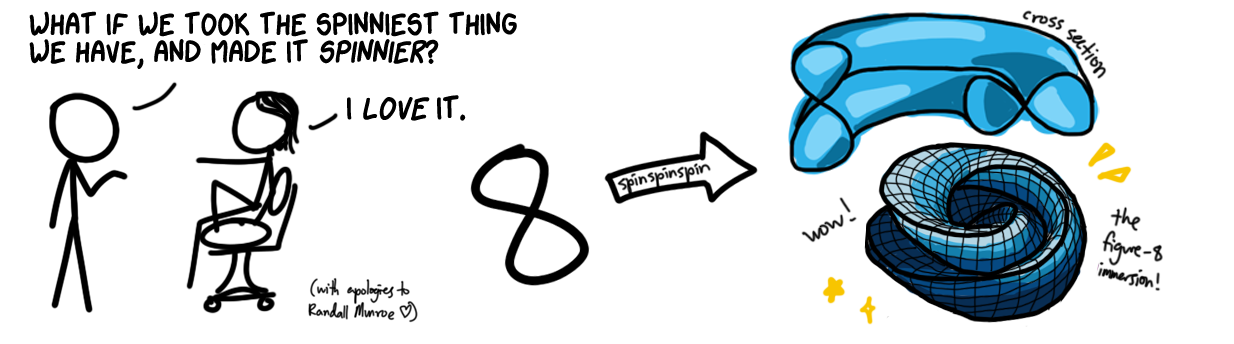

Let’s use the figure-8 immersion, because it’s cool. It looks like topologists woke up one day with a mission to be as spinny as possible: they chose the spinnest shape and spun it around a central axis, while also spinning that shape about its own center.

First, a non-intersecting parametrization of the figure-8 manifold in 4 dimensions, based on that of the flat torus:

\[x=R(\cos{\frac{\theta}{2}\cos{v}}-\sin{\frac{\theta}{2}}\sin{2v})\] \[y=R(\sin{\frac{\theta}{2}\cos{v}}+\cos{\frac{\theta}{2}}\sin{2v})\] \[z=P\cos{\theta}(1+\epsilon\sin{v})\] \[w=P\sin{\theta}(1+\epsilon\sin{v})\]where $R$ and $P$ are constants which determine aspect ratio, $v$ determines the position around the figure-8, and $\theta$ is the rotational angle about the figure-8 and position about the $zw$-plane. (Have fun trying to visualize that!) In this parametrization, the surface doesn’t go through itself because it has that extra spatial dimension that it requires. Thus, this is an embedding of the Klein bottle.

Now, when we take the immersion, we lose a dimension and the Klein “bottle” (or tube) becomes self-intersecting.

\[x=(r+\cos{\frac{\theta}{2}}\sin{v}-\sin{\frac{\theta}{2}}\sin{2v})\cos{\theta}\] \[y=(r+\cos{\frac{\theta}{2}}\sin{v}-\sin{\frac{\theta}{2}}\sin{2v})\cos{\theta}\] \[z=\sin{\frac{\theta}{2}}\sin{v}+\cos{\frac{\theta}{2}}\sin{2v}\]for $0 \le \theta < 2\pi, 0 \le v < 2\pi$ and $r > 2$, where $r$ is the radius and $\theta$ serves as both the angle in the $xy$-plane but also the rotation of the figure-8. Again, $v$ determines the position around the figure-8. The curve of self-intersection for this immersion is a circle in the $xy$-plane.

All this is to say, when we see a Klein bottle we’re viewing a representation of a manifold we can’t fully comprehend.

other examples of non-orientable manifolds

möbius strip

Named after August Ferdinand Möbius, who discovered it as a mathematical object in 1858, although the shape appeared as early as the 3rd century AD in Roman mosaics.

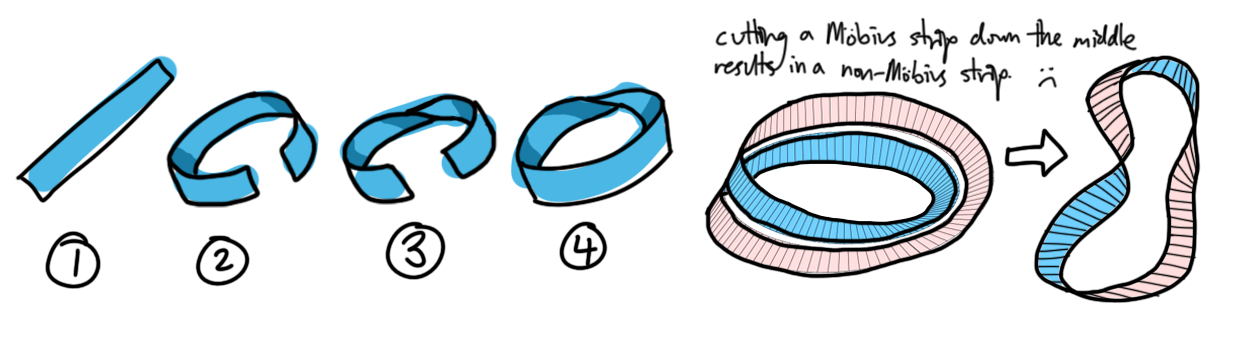

The Möbius strip is probably the most well-known non-orientable surface, since it’s much easier to implement in architecture and whatnot than Klein bottles. You can easily make one yourself by taking a strip of paper, half-twisting it, and taping the ends together. Möbius strips are essentially Klein bottles 1 dimension down: if you cut a Klein bottle in half (if for some reason you’d deface such a beautiful surface), you’d get two mirror-image Möbius strips: a left-handed one and a right-handed one. Interestingly enough, if you cut along the centerline of a Möbius strip, you end up with a perfectly orientable double-length two-sided strip. Unlike the Klein bottle, the Möbius strip is not a closed manifold, does have a boundary, has no self-intersection, and can be embedded in Euclidian space $\mathbb{R}^3$.

In differential geometry, you construct one by taking the space swept out by a line segment rotating in a plane that is also rotating. This is given by the following parametrization:

\[x(u,v) = (1+\frac{v}{2}\cos{\frac{u}{2}})\cos{u}\] \[y(u,v) = (1+\frac{v}{2}\cos{\frac{u}{2}})\sin{u}\] \[z(u,v) = \frac{v}{2}\sin{\frac{u}{2}}\]for $0 \le u \le 2\pi$ and $-1\le v \le 1$, where $u$ is the rotation angle of the plane and $v$ is the position of a point along the rotating line segment. This is another example of a change of variables.

real projective plane

The real projective plane is a compact non-orientable 2D manifold with Euler characteristic 1. It can be immersed (with self-intersections) into 3-space as Boy’s surface or Roman surface, but not embedded.

A Möbius strip is a punctured projective plane, and since a Klein bottle is two Möbius strips glued together, it follows that a Klein bottle is the connected sum of two real projective planes.

roman surface

The Roman surface, or Steiner surface, is a self-intersecting mapping (not an immersion) of the real projective plane into $\mathbb{R}^3$ space. It’s made up of “bulbous lobes,” and can simply be constructed as a sphere under the map $f(x,y,z) = (yz,xz,xy)$:

\[x^2y^2+y^2z^2+z^2x^2-r^2xyz=0\]Another way to construct it, which is more relevant to multi, is by gluing together 3 hyperbolic paraboloids and connecting the edges.

applications of non-orientable manifolds

Since topology is a field so deep in pure mathematics, it’s hard to find actually useful applications of a topic so niche and abstract as non-orientable surfaces, so I’m stretching the meaning of “applications” a little bit to include anywhere non-orientable surfaces pop up in real life, not necessarily applied in any useful way.

Due to their highly recognizable form, Möbius strips in particular have become popular in graphic design and architecture, but there are also some practical uses. Here’s a list:

- Google Drive logo

- recycling symbol

- cutting bagels

- bacon loops

- pasta (goes well with fractal broccoli)

- scarves and hats

- mobius bench

- industrial belts (to wear evenly on “both” sides)

- trihexaflexagons

- dual-track roller coasters

- a world map projection, where there are no east-west boundaries

- the Möbius resistor, a strip of conductive material covering the single side of a dielectric Möbius strip, in a way that cancels its own self-inductance.

- analyzing Bach’s 5th Canon

what's the point?

There are certain topics that are so intrinsically fascinating that you can’t rest until you find out more. The only way I can describe it is the sort of feeling that you get when you learn for the first time that a Möbius strip - or in my case, a Klein bottle - is nonorientable, essentially meaning that it has only one side (a pretty high level explanation). You sort of think to yourself well, that doesn’t sound right. You look at one and start tracing a path through the air with your finger, slowly realizing holy cow, this thing actually does only have one side… how? why?

I think that this sense of awe is universal and everyone has their own topics that elicit that feeling. For me, Klein bottles and the whole concept of non-orientability have been a source of continuous fascination. so I’m excited for the opportunity to share why I think it’s interesting. Nonorientable surfaces in particular are relatively far from applied math, and so my why for choosing to explore them in further depth does not lie in any sort of external use but rather that intrinsic curiosity.

This explanation for why I care about Klein bottles was copy-pasted verbatim from my project proposal.

I also want to thank Cliff Stoll for getting me interested in topology with his infectious fascination with Klein bottles, and Randall Munroe for giving me the sense of humor to enjoy math and science. If non-orientable manifolds are interesting to you, I highly recommend checking out Dr. Stoll’s videos with Numberphile, and if you love science and life in general you should check out xkcd!

references

Abraham Goetz (1970) Introduction to Differential Geometry, page 28, Addison Wesley

Alling, Norman, and Newcomb Greenleaf. “Klein Surfaces and Real Algebraic Function Fields.” Bulletin of the American

Mathematical Society, vol. 75, no. 2, 21 Feb. 1969, pp. 869–872, https://doi.org/10.1090/bull/1969-75-02.

Breen, Casey. “The Classification of Surfaces.” University of Chicago Mathematics REU, May 2017,

http://math.uchicago.edu/~may/REU2017/REUPapers/Breen-Edelstein.pdf.

Chen, Si, et al. “Quantizing models of (2+1)-dimensional gravity on non-orientable manifolds.” Classical and Quantum Gravity,

vol. 31, no. 5, 14 Feb. 2014, https://doi.org/10.1088/0264-9381/31/5/055008.

Coffman, Adam. “Steiner Roman Surfaces”. National Curve Bank. Indiana University - Purdue University Fort Wayne,

http://old.nationalcurvebank.org/romansurfaces/romansurfaces.htm.

David Darling (11 August 2004). The Universal Book of Mathematics: From Abracadabra to Zeno’s Paradoxes. John Wiley & Sons.

p. 176. ISBN 978-0-471-27047-8.

“Electronics: Making Resistors with Math.” Time, 25 Sept. 1964.

Ferréol, Robert. “Klein Bottle.” Klein Bottle, 2017, mathcurve.com/surfaces.gb/klein/klein.shtml.

Freiberger, Marianne. “Introducing the Klein Bottle.” Plus Maths, 6 Jan. 2015, plus.maths.org/content/introducing-klein-bottle.

Junghenn, Hugo D. (2015). A Course in Real Analysis. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. p. 430. ISBN 978-1-4822-1927-2. MR 3309241.

Munroe, Marshall Evans. “Multiple Integrals - Oriented Manifolds.” Modern Multidimensional Calculus, Reprint ed.,

Dover Publications, Inc, Mineola, New York, 2019, pp. 263–268.

Stewart, James. “Section 16.9 - Change of Variables in Multiple Integrals.” Multivariable Calculus, 6th ed., Thomson Brooks/Cole,

Belmont, California, 2009, pp. 1048–1056.

Stoll, Clifford. “What Is a Klein Bottle?” Acme Klein Bottle, Dec. 2021, www.kleinbottle.com/whats_a_klein_bottle.htm.

Wikipedia contributors. “Klein Bottle.” Wikipedia, 6 Nov. 2023, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Klein_bottle.